From architecture to video games

I've been invited to the Video Game Masters, to talk about my career. The french interview is available on youtube. I've written an english transcription that you can read below (with artworks).

I want to mention Marine Macq who invited and interviewed me. She's passionate about concept arts, and the author of great artbooks (Clair Obscur : Expedition 33, Jusant, etc). She's actively trying to bring light to the work behind video games. You can find her work on her Gamma Galery website.

Transcription

Marine Macq: Charles, I'm really happy to talk about your work with you. I enjoyed Caravan SandWitch as well as the other games you worked on. Let's take a glimpse at your artistic path. You wanted to make drawing your profession since a very young age, without knowing in which field. You got your first drawing and design courses in high school. Can you tell us about this very distant time and how your taste for drawing was born?

Charles Boury: Hi! At the begining drawing was just for fun. Then I entered a public high school of Applied Arts. It wasn't classic high school, there was a lot of drawing time. And not just traditional art, it was rather the study of design. I had creative courses in all types of design: fashion design, architecture design, graphic design, and more.

School years

During these 3 years, drawing wasn't the end goal, it was the means, the way to show and tell something, to analyze objects, pictures, spaces, everything. Hence the phrase: "dessiner à dessein" (drawing with intention).

MM: Are there members of your family from the artistic world? Some family member who likes drawing ?

CB: Not really. There are musicians and even lyricists, but no visual artist. Apart from my mother, who took some evening painting classes when I was a child. She taught me watercolor. She later gave me her watercolors box. I still cherish it.

MM: The kind of precious treasures we keep forever. Among the whole range of sketches and drawings you were making in high school, you developped a personal taste for architecture, and joined the École Boulle in Paris, in 2008. What did you learn there, what did you like and maybe dislike?

CB: Paris was a legendary place for me personally, because all my family was born and grew up there: my parents, grandparents... and I had never been there. There was definitely an aura. Artistically also, it's the epicenter of art. A very important place for art schools. Everyone from Toulouse wanted to go to Paris. And I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to go to this school, which fascinated me during the open days.

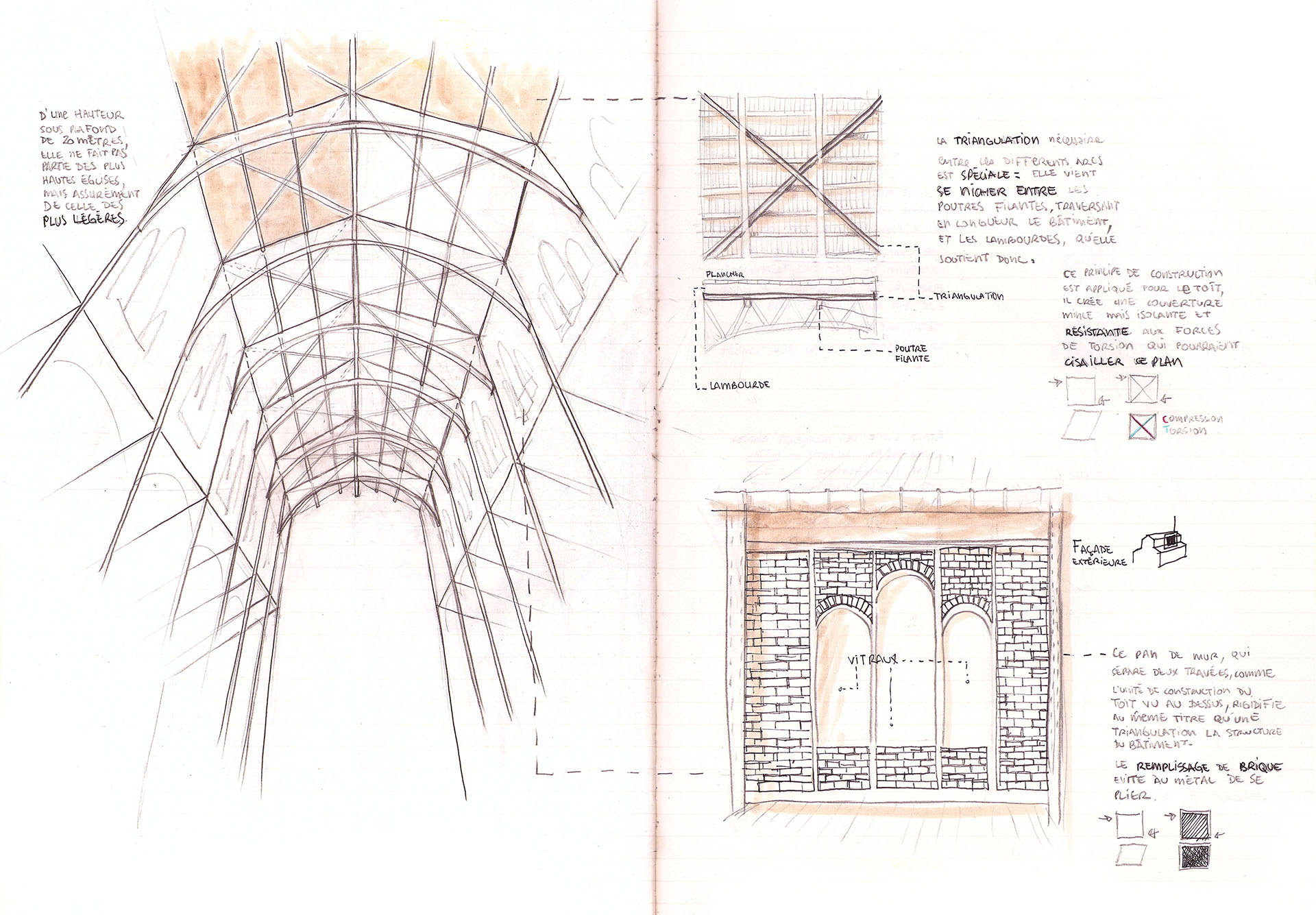

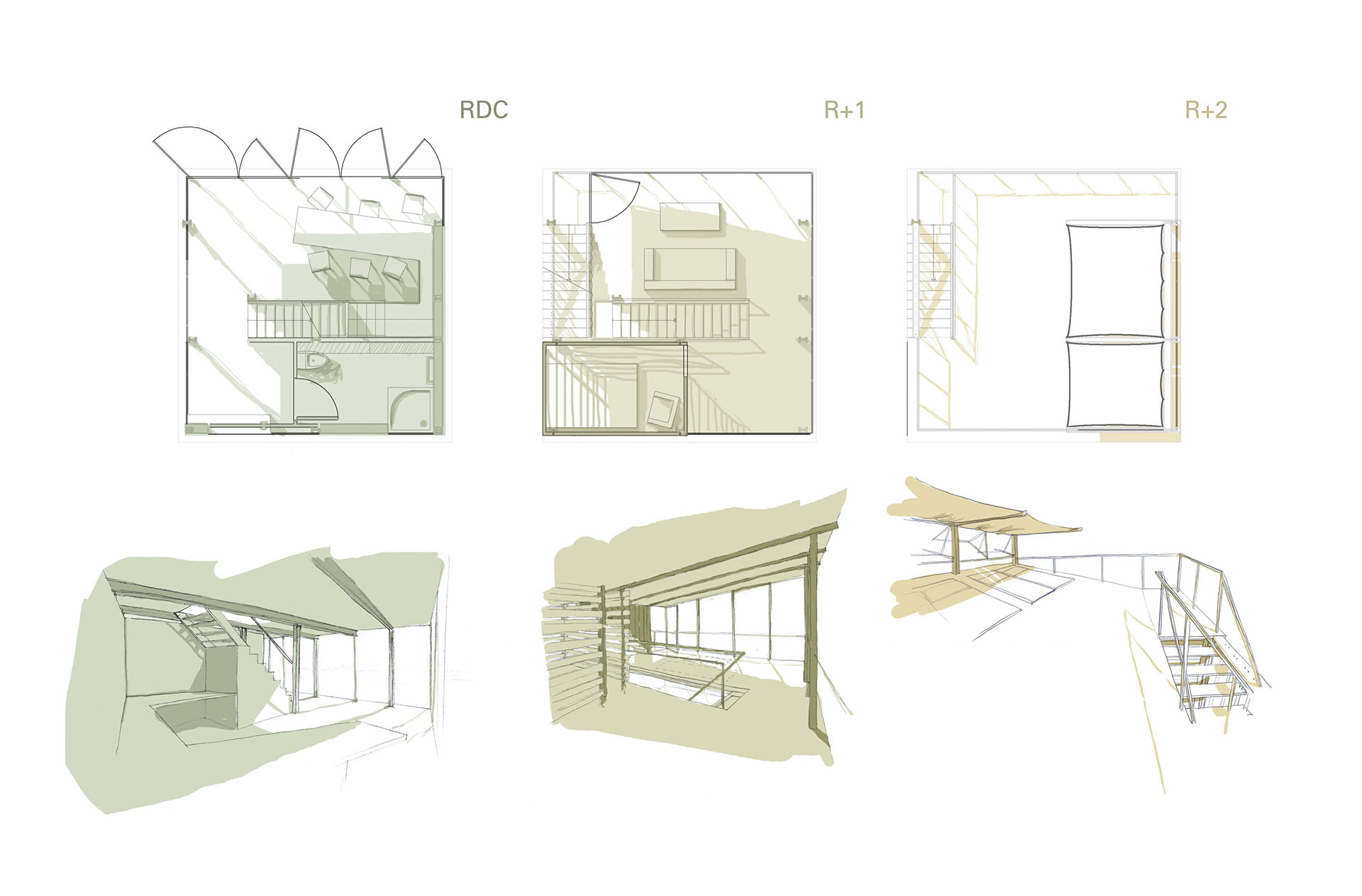

I pursued a 2 years course called a BTS Design d'Éspace (Space Design). It probably doesn't exist anymore. it was kind of an architecture school, but shorter. We had similar courses than what I had in high school but solely focused on space design this time. Space design includes architecture but also interior design, scenography, museography, basically everything that can be walked into.

As you can see, I still loved doing sketches, plain air sketches of Paris. I went to this school because of the last high school assignment. It was a space design creative project. I went so far as making a complete model. It's usual to make models but at that time, I was painting Warhammers. Tiny figures of knights. Moreover, I was also making the game table sets, with tiny cute trees and everything. So for the last project of high school, instead of a regular model I made a whole warhammer-like table set. My project was made of modules, and you could play with it. The teachers loved it. I even got a perfect grade! So I said to myself: "architecture, here I come".

MM: During these studies, you were considering becoming a perspectivist. What is a perspectivist?

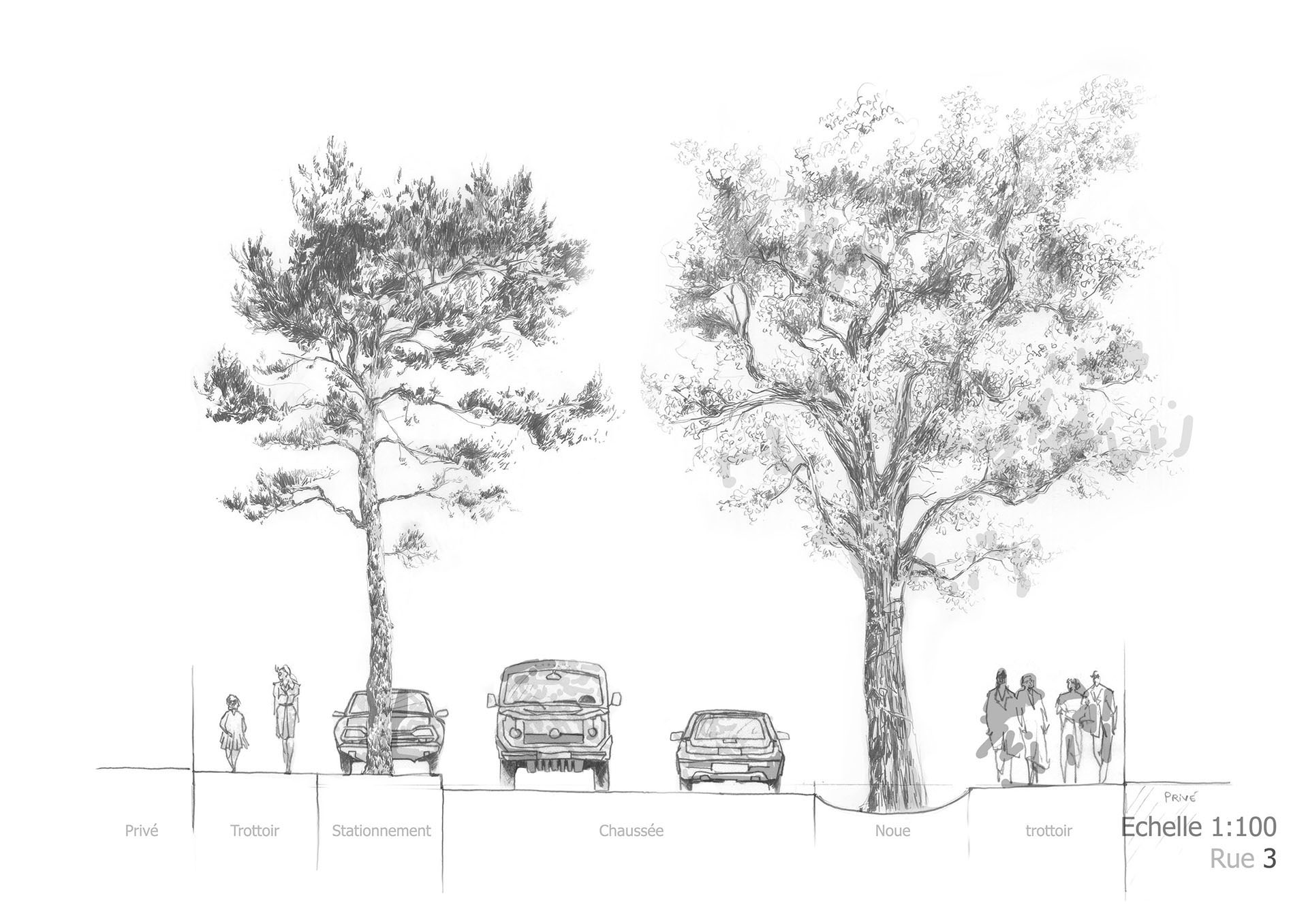

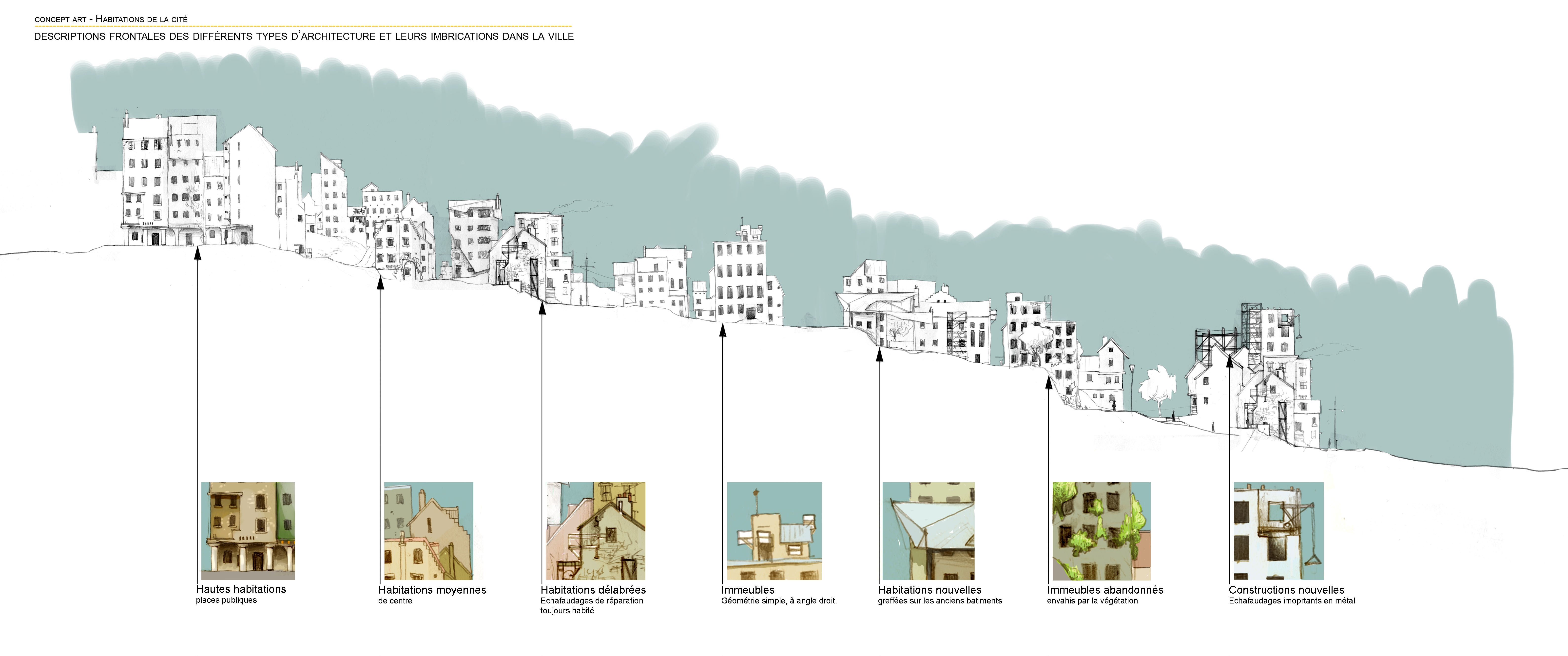

CB: The perspectivist provides visualizations of what the project will be at the end. She typically creates realistic views of the final project, while the building has not yet emerged from the ground. The perspectivist assists the team composed of architects, engineers, etc. She's in charge of visualizations.

MM: Like anticipation drawings? Relying on advices from technicians and architects framing the work?

CB: Yes. It's drawing with intention, once again. Often with a marketing intention: to sell the project, but it can also be a pedagogic one: to show pathways around a building, or to forsee how vegetation will grow. That's important, vegetation! So there are ways of presenting these informations precisely.

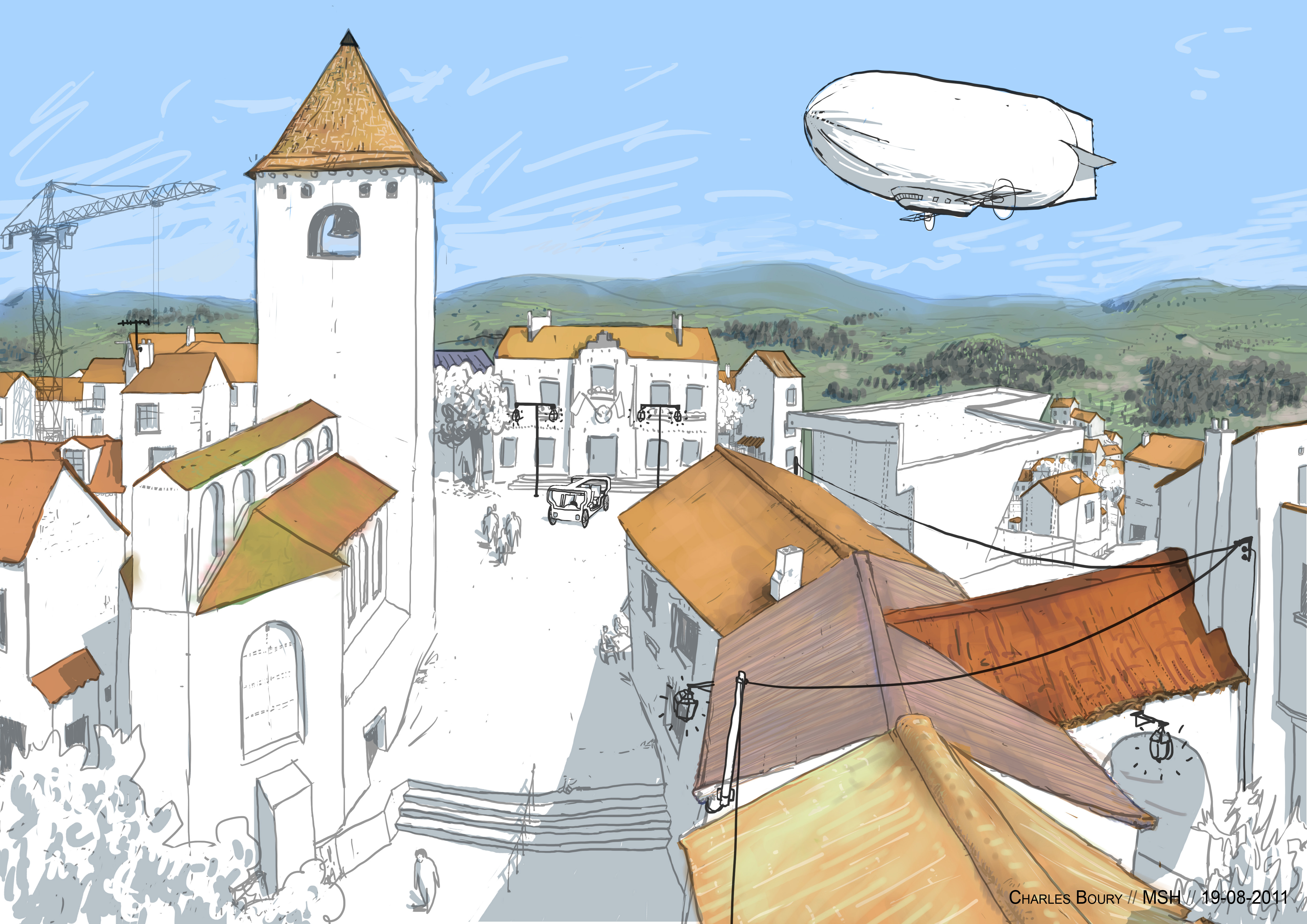

Here is a drawing I did during an internship. So at the end of these 2 years of space design, I got an internship opportunity in a landscaping agency.

I arrived for the interview with all my notebooks. They were quite desoriented, they didn't really understand what I was looking for. The initial proposed internship was not to paint nor illustrate, it was as a landscaper job: to design spaces, to make diagrams, to make plans!

I was very attached to my notebooks at that time. it was a recurring thing: every time I did interviews I arrived with all my notebooks, whatever the job was. So I proposed them to be their perspectivist.

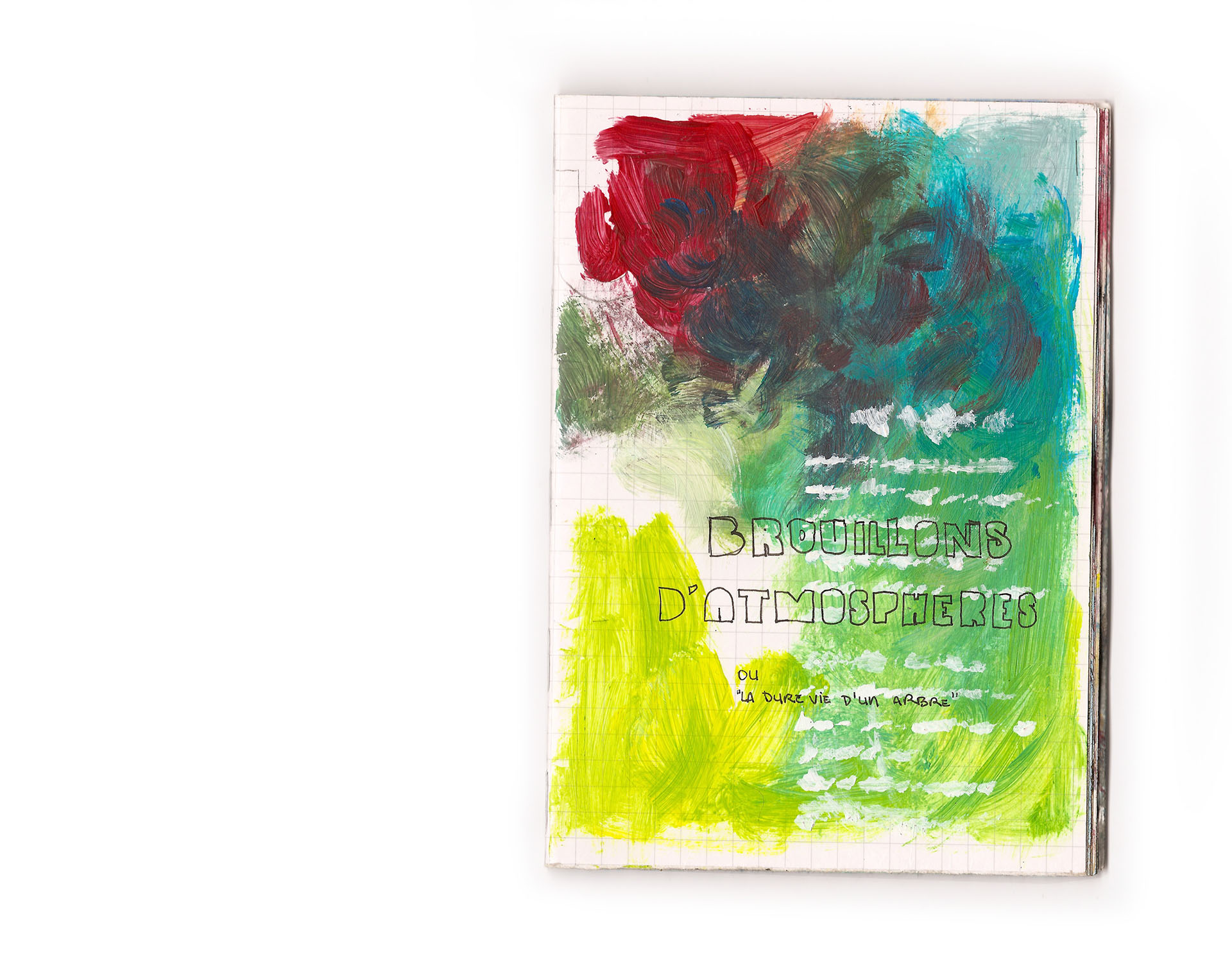

MM: "Brouillons d'atmosphères". It rocks!

CB: I was constantly doing tests.

MM: After your space design studies, you decided to shift to a Game and Level Design Bachelor, at Bobiny. Can you explain how you ended up there?

CB: During the internship at the landscaping agency, I discovered what architecture really was, outside of school. Turns out it's only a week of creative work, followed by a much longer time dealing with difficulties to make it happen. And it can be really long, like 5 or 10 years! So I understood at that time that to become an architect or a landscaper, the deal was to have 5 days of creative work and 5 years of project monitoring. I didn't like that. Not enough drawing here, not enough fun.

I put architecture aside and applied to graphic design schools. I wasn't accepted, unfortunately. A friend with whom I had done my early studies was interested in video games and found a game design course. I followed him.

Serious Gaming

MM: So you were taught Game and Level Design. How did you manage the transisition from architecture?

CB: There were about twenty of us, but I was kind of the only person who drew. Students came from either computer science or general curriculums, whereas I had been drawing and designing since high school. And so I found myself with people mainly interested in video games, whereas I was mainly interested in the design of video games. I felt weird!

MM: Your internship wasn't in a video game studio, strictly speaking. You joined the CNRS on a very peculiar project. Can you tell us more?

Naturally, everyone wanted to join a studio like Ubisoft. We did a one-week workshop class with a CNRS team. The researchers were trying to list how video games could be used to teach things. They were trying to better understand how video games operate.

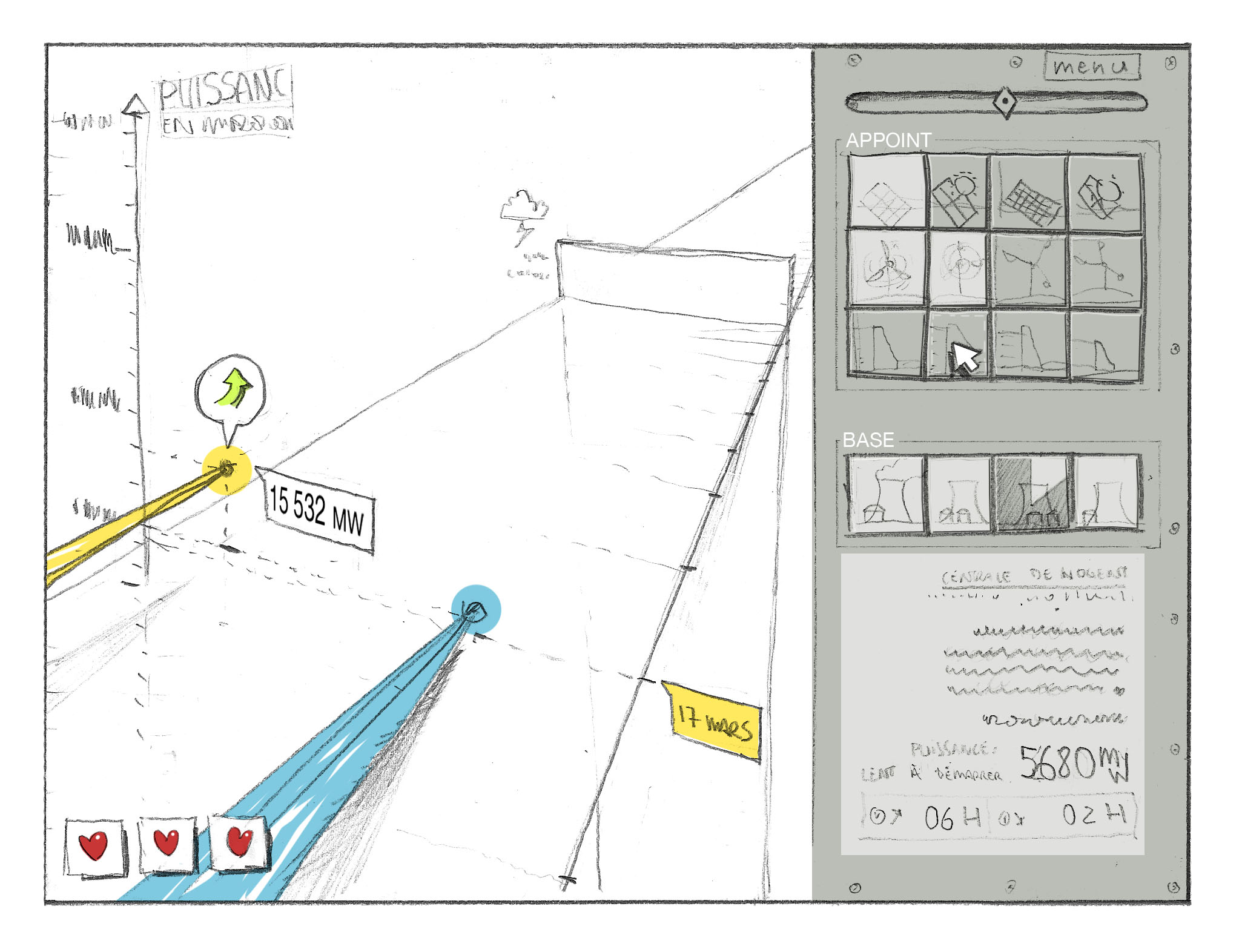

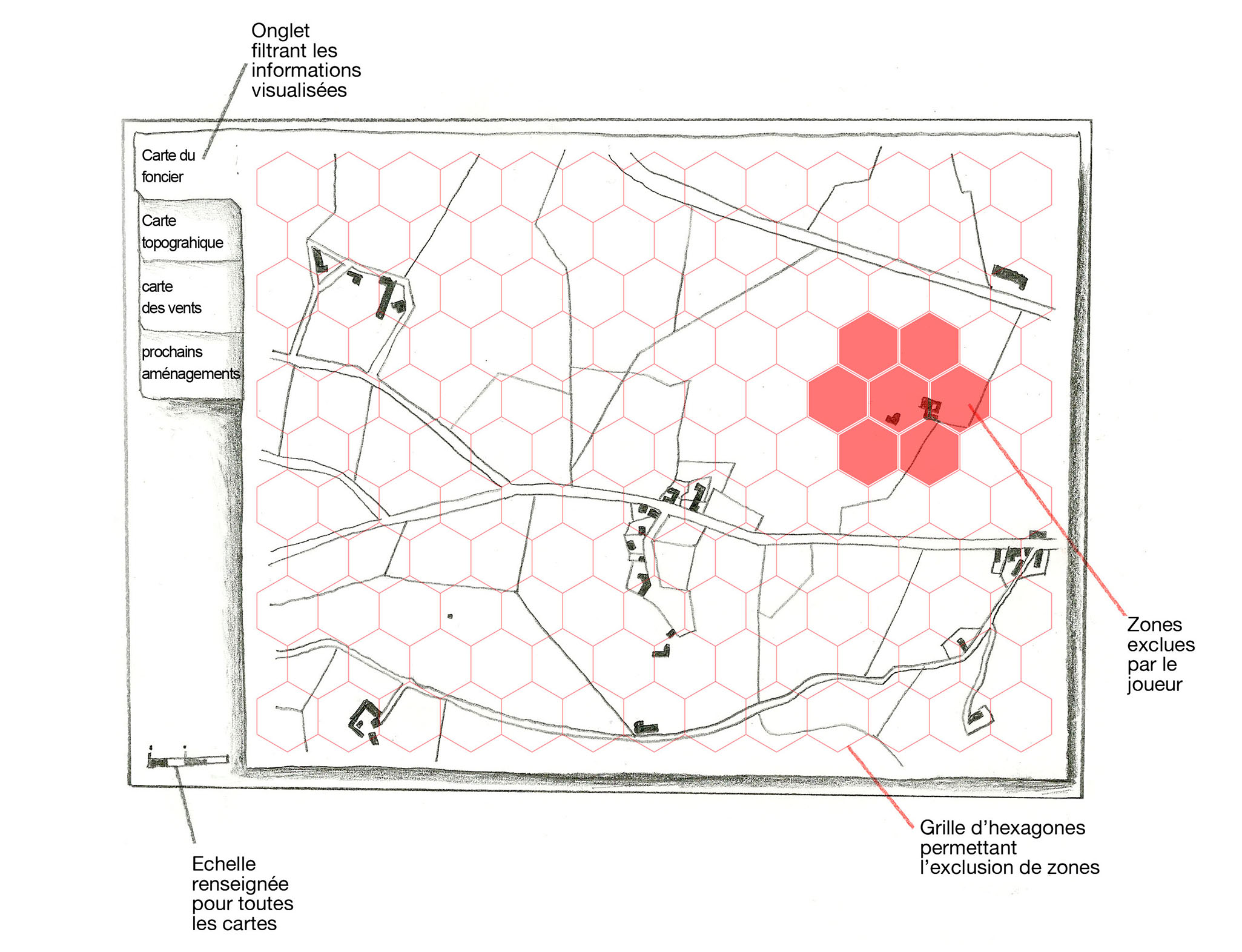

Their game had you play as the energy advisor of a city, a quite derelict city in fact. You were asked to choose what's best for the city's future. Wind power plants, nuclear power plants, water dams... We designed mini-games to play with energy types pros/cons and to explain territorial stakes around the city. I'm the only one who reacted positively to this thing. I loved the workshop and I immediately applied to an internship with them.

MM: So that's how you ended up at the CNRS, doing urbanism in video games.

CB: As a level designer.

MM: It's unusual!

CB: Yeah it was a bit chimerical, a bit fun.

MM: By the way, you didn't go to this Game Design course just to follow your friend I guess. What was your relationship with video games?

CB: I played games as a child: Zelda, Mario, Final Fantasy, Gran Tourismo. Quite a few. Then during my studies... Let's say I had a moment where I played World of Warcraft a lot and I had to stop.

MM: You were getting sucked in there.

CB: Totally. I nearly failed the year before bachelor. So I put that aside. I liked video games, yes, but I had never planned to make them. I saw myself in more serious design fields.

MM: So you discovered the field of Serious Games and then worked in it for several years, joining a Franco-Norwegian game studio. What was your role, and on what type of game did you work?

CB: After the CNRS internship, I couldn't find a job in video games. So I looked for another Level Designer internship. I joined the team at We Want To Know. They had already released a serious game to teach maths and were planning a sequel.

MM: So I guess it's not for me!

CB: Oh but yes, precisely! What I really liked with the game, called Dragon Box, is that you don't realize you're learning maths. It's very cunning. You've spent the whole game moving little critters left or right, made them disappear or reappear to clear each level, and at the end, you learnt how to solve equations. Without realizing it. It fascinated me because it was once again the work of design. How to control the effects of a device. It's the direct continuation of what I was doing on architecture or fashion design.

At the end of my 3 months internship, there was no place for a level designer. On the other hand, the studio was looking for a Graphic Designer. They accepted me for a test period and that's how I finally became a real graphic designer.

I created visuals, UIs, FXs and anims for puzzle maths games, but not only. The last game I worked on was to learn chess: a 2D open-world chess game.

Focusing on the picture

MM: After more than 4 years on serious games, you decided to try something else, and focus on illustrative works. Can you tell us more about these traditional blue watercolors?

CB: I wanted to try other things and really get better at illustration. Well, I tell myself that now but at the time I didn't really know what I wanted to do. I tried web design, 2d animation, and lots of other stuff.

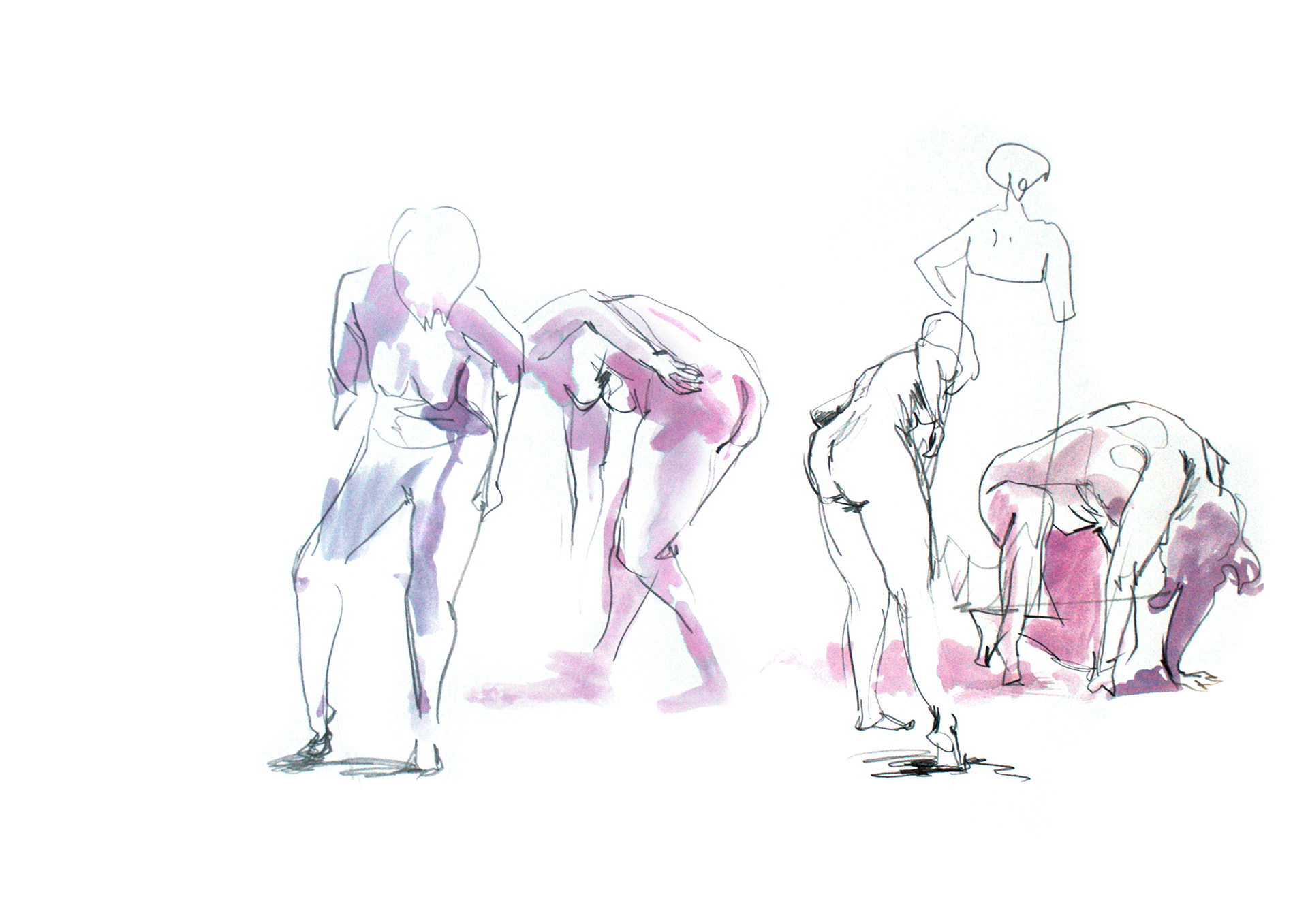

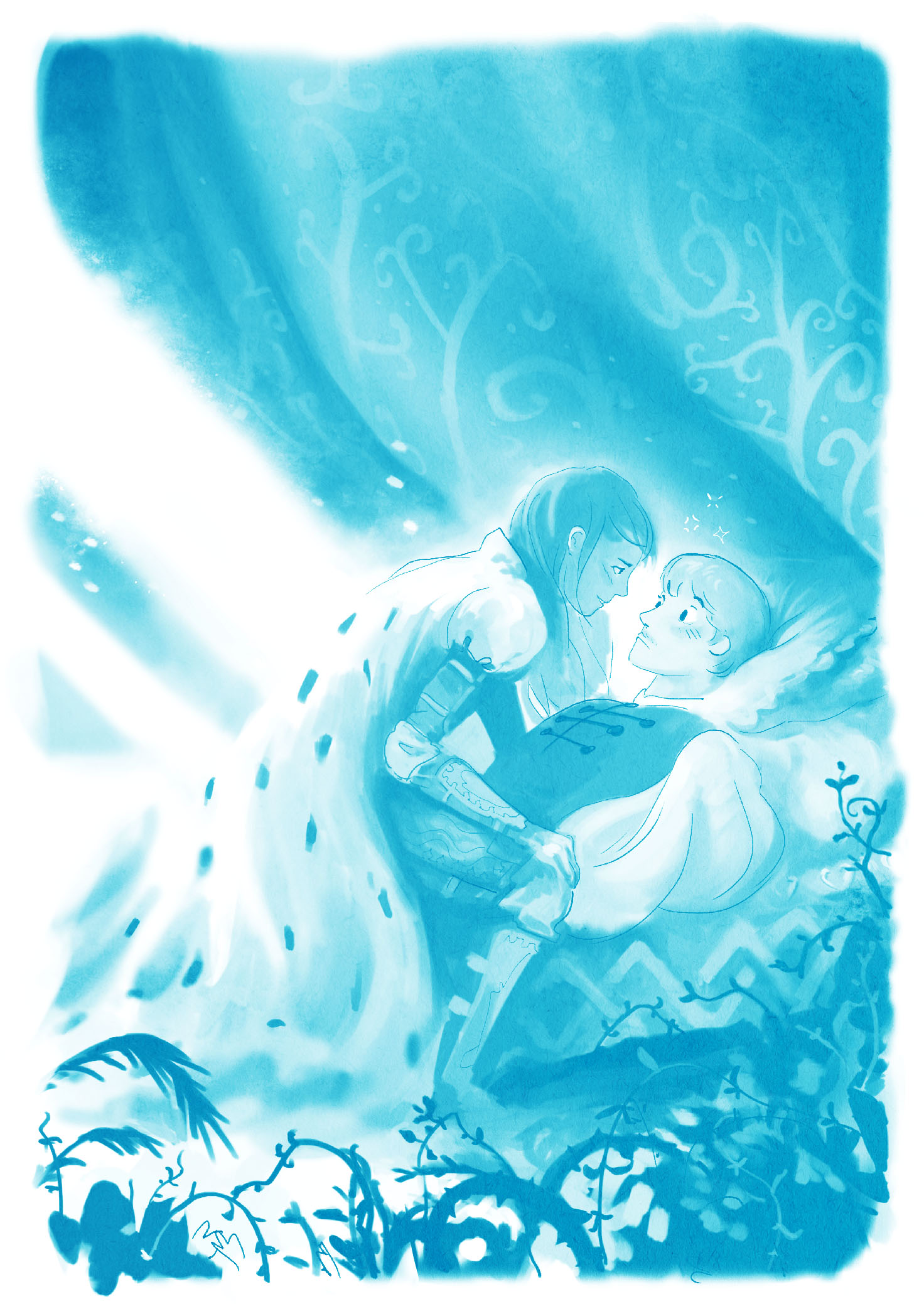

One of these experiments was with another friend, Lucile Nicosia, who's been an architect for a few years but also decided to leave the field. She was then pursuing gender studies. Gender Studies is what is socially happening around gender, lots of things to say about that. Our commoun idea was to swap genders in fairy tales and see the result. Fairy tales are heavily gendered, with very stereotypical roles, as you know. We called it Les Contes bleus (blue tales).

Lucile wrote the text, I drew the illutrations. We worked on "Le Beau Au Bois Dormant" (Sleeping handsome), the knight-woman arriving all frisky on her horse, looking to free the poor indolent prince. Also, it's not traditional watercolor! It's digital, but it's the watercolor brush.

And there is something special here, it's that it's all blue. Our project was commissioned for a book that was printed only in blue. So there were text pieces about the Smurfs, the polluted ocean, and more. Did you know that "Blue tales" is another, outdated way of saying fairy tales?

Also, the watercolor graphic style is not gratuitous. There's an intent behind it. I wanted to reference drawings from Fragonard. He's painter from 1700s. The ink wash paintings of Fragonard were rather brown than blue. But he was often depicting scenes of frolics, sensual kisses under the bushes. It was interesting to take up his style and apply it to question gender. Fragonard illustrations are a bit shocking today. it's perhaps an outdated eroticism, but his drawings give the impression that the women say no.

MM: The style is quite comparable to the notebooks we talked about earlier. You've always switched between digital and traditional? you've always liked both in your practice of drawing?

CB: Well there was a time when I struggled to learn digital. The transition was complicated. But when I managed to switch, then I kind of gave up on trad...

MM: Is that true? Do you regret somehow?

CB: I'm not proud. Each new year, I plan to start making notebooks again.

Technical diving

MM: So illustrations, web design, but also programming! I discovered that you remade the first Zelda in your style, the one that came out on NES in 1986. Why did you want to get into programming?

CB: Programming is a big subject. As a designer, I believe that you need to know your medium. An architect needs to know material resistances. A graphic designer must know how printing works. But for video games, it's a lot of skills. I had the feeling of not really knowing my craft. So I wanted to learn it, even if it seemed really complicated at first. Programming really seems obscure.

I stumbled upon the work of a brillant guy named Bret Victor. He's a programmer but above all, he's a UX design researcher. In fact, I discovered him when I was working on serious games, looking for references on how to explain complex things. Bret Victor was proposing ways to better explain programming. He was making tools, toys. It was not that complicated when you knew how to visualize it. These tools helped the programmer visualize the code state. It was awesome, Bret Victor is really awesome.

So as a self-taught programmer, I needed to find myself a little challenge. The ability of a self-taught person is to pick the right kind of challenges. Little challenge, little reward, new skill, etc. Well this project was too big. My bad. Remaking Zelda 1, even if it's from 1986, it was too big. So I decided to reduce it to just 4 screens, but it was still too big. So I only made one enemy and I didn't even make the chest. The project is called Gabrielle. So yeah, the goal was to learn programming, but it wasn't just an intellectual exercise, but also to display something different on my portfolio, a game that wouldn't be a serious game, that would be appealing to game studios.

MM: It's quite funny because you discovered the next project a bit by chance. A game studio called Labelle Games was planning to design a video game adaptation of a well-known novel. They were looking for an artistic director. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

CB: At that time I tried to be in the right discussion groups. That's how it works, you have to be in the right place. So I managed to enter one of these discussion groups, where all the cool gamedev diaspora of Paris was slacking.

I had been lurking for a few days in silent mode, just reading messages, and I see one telling to everyone "we are looking for an artist, one with the same style as Charles Boury". Well... I guess I can try having the same style as Charles Boury!

I think they saw my zelda game and decided I could correspond to what they were looking for. Even if, in terms of artistic direction, Frankenstein's Creature isn't the cute little thing we saw earlier.

MM: How to build the foundations of an artistic direction for a novel adaptation?

CB: I have to pitch you the project then. Quickly. Frankenstein's novel is special, it doesn't really press on the creature monstruosity. There's an enduring vision, from the cinematographic adaptations, but the novel is different. It's a tale written through the eyes of the creature, who discovers the joys of being alive, and also the horrors of being rejected, managing his own anger, etc. it's a romantic novel, meaning: it gives a large place to emotions, unbridled emotion.

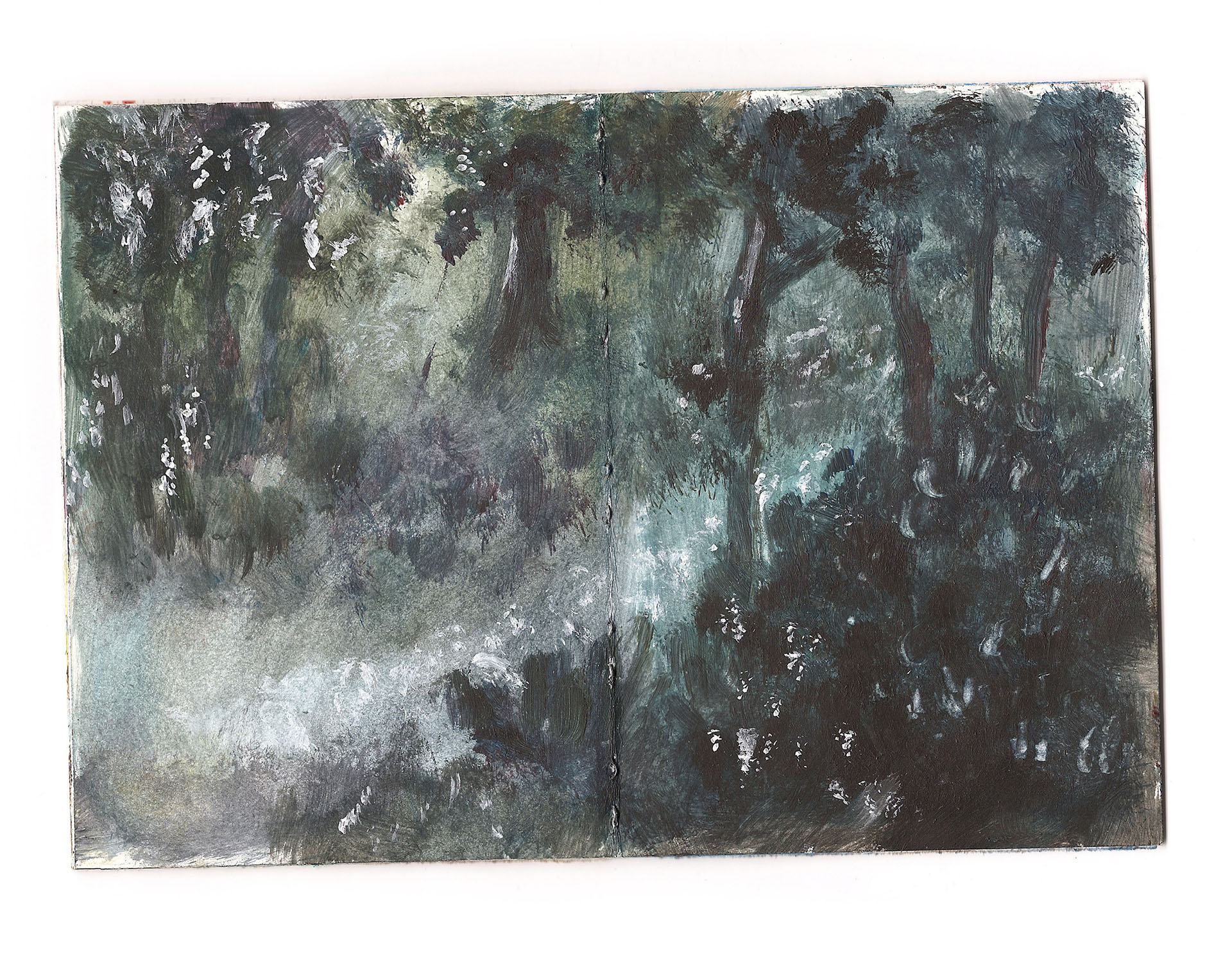

So I drew from romantic paintings. It's the same name because it's the same underlying philosophy: when Caspar David Fredrich wants to depicts some windy beach, he paints an 8 meters wave. Unbridled sensations. So I drew happily from all this, all this vocabulary of colors and touches, as if we were in a moving 19th century painting. The character occupies 5% of the screen at most, to be swarmed by the world sensations.

MM: It was your first time as an artistic director on a project. What was your working method, your creative process to give shape to these romanticized, grandiose settings?

CB: It was kind of the dream project for me because I wanted to have a bit more fun with the graphic work, and the pitch was to make bombastic paintings. It had been decided very quickly that the character was going to be very small, in order to minimize its monstrosity and to orient the point of view towards the outside world. The game is a point and click adventure, and I only knew how to do 2D. Well, the character is 3D but he moves on a setting which is invisible, and behind, there's a big flat texture.

There are several steps. First there's kind of a moodbard, to get color ideas, shapes, etc. Than I make a rough, a quick one. Don't look at the details. There aren't any.

Then I expand it, to see what the level could look like and we go back and forth with the game designers to establish a rough placement. Once the team is settled on the general shape of the level, I then spend time to make the little details. I paint. it is supposed to be well zoomed out but the camera nonetheless moves through the world. Another game feature was to have several variations of the same settings, to toggle between emotions based on player actions: the awe inspiring concept of a divine entity, or the despair of permanent death.

MM: The first chapter of the game is very pleasant, as the creature discovers the world. The player traverses very refined paintings, lots of white, and the paintings goes up in color slowly. Did you defined it through storyboards?

CB: Definitely. We tried to conform to the sequence of actions in the novel. We were forced to make cuts but the start of the novel is like that: the creature becomes aware, doesn't understand what is happening, what's in front of it, touches things, stumbles upon stairs, etc. I tried to get a visual representation of the discovery of the senses.

Chapters passages are also cool. In the novel, it's a moment where the set moves, almost like a theater: new act. I had fun doing these moments of transition.I used some layer juxtaposition tricks to visually signify an ellipse. I often make fake mockups, to pretend. I use Photoshop to render a video of moving layers.

Taking the highway

MM: You then worked on Road 96, which was quite different. It was a total discovery for you, on lots of aspects. You met the game creator, Yoan Fanise, during a Game Jam, right?

CB: I love participating at game jams. This one was organized by Arte Interactive (the european public service channel dedicated to culture). Usually, Game Jams are not organized by Arte. More so by people who like platform games, saying "let's make platform games!". I had to apply. It doesn't happen like that, typically. By the way, Arte was one of the producers of Frankenstein.

MM: They produced Frankenstein, yes.

CB: Yes, but I haven't had strings pulled for me, I swear! I applied and got accepted. There were 60 of us. So we set out to do a Game Jam over a weekend and I found myself in a team with Yoan Fanise. This guy worked on biiig games at Ubisoft, and now was directing his own indie studio. We matched, and at the end he pitched me his project which was in the preproduction phase: a procedural 3D game with several possible stories depending on player choice.

So I joined the project as an Artistic Director, at the start of production. And indeed, it was a challenging project, because this time, it was in 3D!

Also, we were a small team, it was essential to be efficient. I had to produce 3d assets. After shipping Frankenstein, I had improved my 3D skills a little bit on small projects, and presumed that it was enough. I would learn the rest as I go.

Here's what's crazy with Yoan: the beginning of production means that the game is already done. You can play it, it's already there. Some bugs here and there, it's not very beautiful, lots of things to polish, but you can play it from start to finish. I was given the controller in my hands, on my first day. 8 hours later I finished the game. I was so on board.

The team had a year to polish it. When I arrived, there were placeholders everywhere, robotic dubbing, etc. The problem with this is that now, well, there's a very precise schedule. One week to do this, one week to do that, and so on. No delay possible! So my idea of learning 3D as I go wasn't so great. But we did well, the team was so capable, everyone was great at their job, I learned a lot and we got terrific reviews.

MM: I suppose there were a lot of paintovers if there was already a playable prototype? You worked based on something already there?

CB: Yes, the artwork above is a paintover I did it as an art test. They gave me a screenshot of the demo that I painted over. An artistic direction was already established by Yoan, a bold one. It was another challenge: to conform to this artistic direction and assimilate it.

The game puts you in the shoes of a teenager who tries to flee an oppressive, dictatorial country. You flee by hitchhiking, and so you meet people, more or less nice, in a harsh world. There was a small list of things describing a visual direction, which I expanded upon.

I drew from Americana - the USAs in the 60s, but also from USSR, to make a good matchup of oppressive countries. Countries selling dreams and giving rubber baton beatings. I also poured from early cold war propaganda. Also pulp comics and beatnik inspirations, to bring the point of view of the fleeing teenagers.

MM: For the previous project, they came to you for your style. Here, it was necessary to conform to a style. Was is the biggest challenge of this project?

CB: Absolutely. I first started with my cute little drawings, my light rays and uh... It didn't work. I needed to assimilate this style. An there was also this technical challenge, being the artistic director but not knowing well how to do 3D modeling, as quickly as my colleagues... I had a hard time finding my place. So I put all my energy, all my know-how on the 2D parts: posters, textures, interfaces... If you played it, I hope you noted the interfaces. The teenagers point of view is rock'n roll, and this feeling is experienced through UIs. Through dialogue choices, menus and mini-game UIs. We spent some time on that.

MM: Charles, thank you for this glimpse into your career.

The interview was followed by a presentation on the Art Direction of Caravan SandWitch.

Thanks for reading! I hope it was informative. If you want to see more artworks, look at my portfolio.